A Washington-based sociologist returns to Romania, 80 years to the day after the murder of 13,000 Jews in one of the first Nazi-inspired mass killings of World War II.

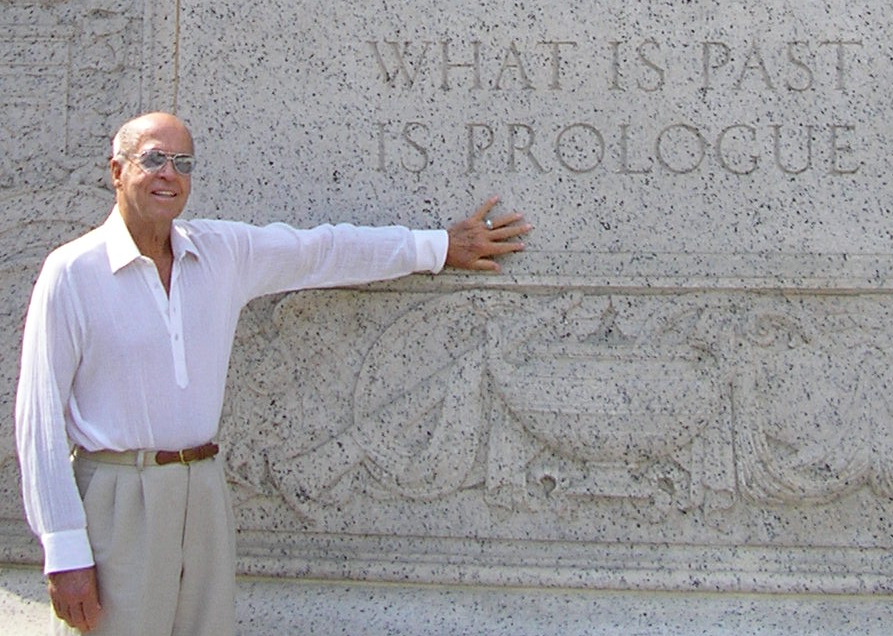

Peter Eisner

Eighty years ago this week, the childhood of a 10-year-old Romanian boy faded in horror. A murderous mob shoved Little Michael, his mother, baby brother and one of their grandmothers face first against a church wall.

“Ready!” called out the gang leader, and Michael could see nothing, he heard only the raspy voice and the sound of weapons being primed. “Aim,” the disembodied voice called out. And after a pause, the final well-known word only waited to be formed on the tongue and uttered in the brutal morning air. Beyond fear as he awaited darkness, Michael heard a commotion. A different voice this time, an unknown savior.

“Let them go!” Michael would never know why and assumed the man could have been a Romanian army officer. Was it mercy or a concern about staining the church with Jewish blood? Gratefulness and mercy were complicated—he could be thankful despite it all that this man had interceded and before the gang leader could cry out: “Fire!”

Michael Cernea, 90 years old, is hale and embarking on the next step of his life journey. A celebrated sociologist, Cernea has dedicated his life to the underserved and immigrant poor. He essentially founded the sociology department at the World Bank, where upon his retirement two decades ago he was praised as the trailblazer he was. And behind it all, the horrors of a childhood that could never be erased.

Tuesday, June 29, 2021, a commemorative event was organized to follow the steps of a forced march that has haunted Michael Cernea these years since. In late June returned to his home city of Iasi [pronounced Yash], Romania, where the unimaginable became real. He was a witness and survivor of a largely unknown event, the murder of 13,000 Romanian Jews over four days at the start of World War II.

The European Union changed travel rules under COVID restrictions at the last moment for the vaccinated and he was able to travel from Washington, D.C. to join the commemorative march. There were roadblocks along the way, but finally the Romanian government invited him to come. He will be declared an honorary citizen of Iasi, almost 50 years after he defected from then Communist Romania to the United States. He lives in suburban Washington, D.C., though his thoughts are never far from those days in Iasi.

Cernea lived in an apartment off a courtyard on Colonel Langa Street. Early on Sunday morning, June 29, 1941, he peered out from his house through the spaces in a fence toward the street. People were marching under armed guard, hands in the air, men, women, children, infants carried in the arms of their mothers and fathers. The shadows of memory persist.

“We were in the house and we saw that there are columns of people moving on the street. We didn’t know where they were going, but we recognized there were Jewish people in those columns, so we understood that something bad had happened.”

Before long, soldiers and men in civilian clothes barged into the house. “Out, out, all Jews out, all Jews out.”

Michael, his father, mother, his brother, and grandmother all were driven to the street.

“We had all to go with hands up. My brother was two years old, so he could not move fast, so my father put him on his shoulders. But my father was supposed to keep his hands up, and that is the image I see before me, my little brother, with his little hands up, my father’s hands up, the little legs clinging to his shoulders.”

Who were the other survivors who had come to Iasi for the 80th anniversary of the pogrom? Surely, in their silence, all would recall the corpses and the mortally wounded who lay where they had fallen, people jeering from the side of the road who were throwing rocks and insulting them, rifles jabbed at those in the march who did not move quickly enough. Screams, the sound of babies crying, people wailing as they marched along.

Here, where Romanian fascists and Nazi overlords herded him and his family to the police station. Here, somehow, he survived that day. So many others did not. He would bear witness for them. Every day in the years since, he would close his eyes and see what he saw on that march. He escaped and went into hiding, but in less than a week, 13,000 Jews were butchered, tortured, left nameless and almost lost to humanity. Cernea says it is his responsibility and of all those who survived to speak out and to speak of the savagery they experienced. Their numbers dwindling every day, the urge to tell the story grows.

Cowering and subsisting for more than three years, Cernea and his family eventually fled to Bucharest, the Romanian capital, after D-Day, but the ordeal was decades from being over. In 1944, he and his family cheered as Allied bombs fell all around and nearly killed them. The Soviet Red Army advanced into the country and installed a Communist regime that downplayed the Romanian Holocaust. The fascist dictator Andrescu and his henchmen did face war crime trials at the end of the war, he and others were executed in 1946. But while the stories of the Warsaw uprising and the concentration camps of the Third Reich were often told, the massacre at Iasi and the plight of Romania Jews was mostly hidden behind the Iron Curtain for decades.

Michael Cernea left Romania for the United States in 1974 and was able to extricate his family with official help. He became an internationally recognized sociologist who pioneered the impact of social science on the World Bank. He created a team of dozens of sociologists and anthropologists who studied the impact of development in the Third World. His goal was always to improve the lives of the world’s underprivileged poor. All the while, he was remembering a childhood that almost ended facing a wall with orders that he be murdered. Grateful all the while that he had survived, of course, but also mourning those who died. He feels a responsibility to serve their memory through his contributions to the world.

June 29, 1941 was a mild morning and the killings had already begun. The march toward death had its roots in long-lasting antisemitism in Romania, the rise of Romanian fascism, and the growing affinity between the dictators Marshall Ion Andrescu and Adolph Hitler. Andrescu had joined the Axis with Germany, Italy, Japan, and other smaller countries in 1940 and was committed to the cause. For Hitler, an assault on the Soviet Union was the immediate goal. When Hitler, aided by Romanian troops, invaded Russia on June 22, 1941 – a week before the forced death march – Iasi, Romania’s second largest city, played an important logistical role. It was less than 60 miles from Russia’s southern border, but eleven miles from the border with the Romanian territory of Bessarabia, which had been occupied by Russia. Iasi had become the war front, subject immediately to counterattacks by Stalin’s Red Army.

There was no escape, not Russia to the north, nor Hungary to the west or Poland further north, both occupied by Nazi Germany. Word of war with Russia had come directly from Marshall Antonescu, Romania’s leader. “There was an announcement…very dramatic announcement of Marshall…everybody heard it, and the war started,” said Cernea. “The town was already full of military, Romanian and German, it was obvious to everybody, imminent that something will start sooner or later. Everybody was frightened to death.”

Two days after the declaration of war, the Soviet air force attacked Iasi, causing little damage or injuries, but prompting war hysteria. On June 26, the Soviets attacked again with deadly force, killing at least 100 civilians, perhaps hundreds more among them at least thirty-eight Jews. Nevertheless, the Jews were blamed.

Unfounded rumors circulated that Iasi Jews were spying for the Russians and had been sending signals to the enemy. The city’s 40,000 Jews had already been designated as “enemy aliens, Bolshevik agents and parasites.” They had been systematically stripped of the ability to work and lost all privileges of citizenship. Now, with the invasion, the local branch of the ultra-rightwing National Christian Party joined forces with Andrescu’s Secret Intelligence Service to create a systematic blueprint for rounding up Jews, deporting them, putting them to work, or just killing them.

The plan was mercilessly efficient, so successful that the Romanians were overwhelming themselves with captured Jews, who were forced to march to police headquarters from throughout the city. So many people had been drawn in that something had to be done; there was potential danger in so many Jews in one place with not enough guards to control them.

“So, when we were brought in, our turn came, they used triage, a selection. They kept all the men and the taller boys and sent women back with their children like me. They pulled my father in, and they waved the rest of us all back. I tried to reach out to him, but he pushed me away as the gate closed.”

Now the rest of the family ran home, screaming and crying all around them, carrying the fear that Michael’s father might be killed, but all the while running a gauntlet of insults and rocks and shovels beating at them.

“We almost made it to our courtyard, where we would hide, we were almost there. By that time there were more corpses, I remember seeing more corpses laying on the streets, blood everywhere.” But as they approached their home, a gang of men stopped them at gunpoint – some of the civilian paramilitaries from the Christian Front, he guessed, if they were not just murderers taking advantage of the blood and chaos of the streets.

“Ho there,” said one, while they shoved and poked them with rifles. “Where are you going?” The police have called you.”

“No, no, no,” pleaded Michael’s mother. The women around her began to pray. “They have sent us home.”

“No, no, no,” shouted the leader of the group, which by now had gathered up some of their neighbors, the Zilbermans and the Barads who also had been released, but only the women and younger children. “Up against the wall.”

They shoved them face first against the wall right across from their courtyard, ironically the outer wall of the local Catholic Church. Time was fleeting, childhood had fallen away, he felt his mother’s warmth and love as she held his little brother who was weeping, his grandmother who was praying, and the others, even Zolly, his playmate, and the little girls who were often in the yard with him. Childhood had gone. He could sense the end of his days. The world had narrowed to contemplating the contours and grains of rock built into a church wall. There was nothing else.

It took weeks before the full scale of killings was known. Hundreds were killed that first day on the march and at police headquarters, but thousands more were rounded up and forced onto cattle cars at the Iasi train station. The assumption was that these would be used as slave labor for the German Reich and occupied territories, but the reality was worse. The Romanians sealed the ventilation holes on the train cars, jammed people into the freight cars without room to move and drove them in circles around the city for three days, occasionally halting so those still alive could dump out the dead. Jewish work teams then were forced to dig mass graves for the fallen. More than a third of the Jews of Iasi had been killed in less than a week.

Radu Ioanid, formerly a researcher at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington and now Romanian ambassador to Israel, described the train car killings: “some captives tried to get a drink by tying many strips from their shirts into a kind of rope, which they then tossed from the railcars toward nearby puddles to sop up water.” Ioanid gathered photographs and testimony at the museum. The fact that he now represents Romania as a diplomat is a sign of change and reconciliation. Ioanid is a historian, author of The Holocaust in Romania and The Ransom of the Jews (Ivan Dee, 2005), and one of his country’s prominent chroniclers of the Holocaust.

One of the survivors of the cattle cars, Nathan Goldstein, described the scene in an oral history collected by Beate Klarsfeld. He said that the panic and thirst was overwhelming. “They would jump out through the small opening of the car to go drink the water. Most were murdered by the soldiers…an eleven-year-old child jumped out the window to get a drink of water, but [an official] felled him with a shot aimed at his legs. The child screamed, ‘Water, water!’ Then the adjutant took him by his feet, shouting, ‘You want water? Well, drink all you want!’ lowering him headfirst into the water of the Bahlui River until the child drowned, and then threw him in.”

These were the first days of the war in Romania. Between 1940 and 1944, at least one quarter of a million Jews in Romanian territory (some estimates approach 400,000) were killed by German, Romanian and other Axis forces. After the Iasi Pogrom, rampages and other pogroms occurred in the state of Moldovia, where Iasi was located, and also in the neighboring states of Bassarabia and Bukarina.

Michael Cernea recognized the significance of the moment. “It is a difficult story. I think it is important that the story be known. It is the story of one person’s life which intervenes with history at a crucial juncture of history. I hope that it may become more relevant for broader purposes of identity and of faith, of history, of social and political change. I hope that my children’s children’s children and so on will sometime learn this story and they will know the history behind it.”

was doing during the war. I knew he was an officer on LST 463 in the South Pacific. But he only told the funny stories and sidelights. Nothing serious.

was doing during the war. I knew he was an officer on LST 463 in the South Pacific. But he only told the funny stories and sidelights. Nothing serious.

ad used his engineering skill to figure out the parabolic movements of ordnance in the air, drawing imaginary lines to shoot down a diving airplane. He shot down two or three zeros.

ad used his engineering skill to figure out the parabolic movements of ordnance in the air, drawing imaginary lines to shoot down a diving airplane. He shot down two or three zeros. urvived the Philippines, but I went to the memorial wall to look for familiar names. I found one man with my last name. Jacques Eisner from New Jersey where my dad was born. Born in 1919, just like my dad, died back then during the war, never made it beyond 25, out there in the Pacific.

urvived the Philippines, but I went to the memorial wall to look for familiar names. I found one man with my last name. Jacques Eisner from New Jersey where my dad was born. Born in 1919, just like my dad, died back then during the war, never made it beyond 25, out there in the Pacific. Researching my book, MacArthur’s Spies, I tracked down Claire Phillips’s wartime diary, written in a small insurance company date book. This is the first of a series of blog entries featuring the diary — untouched for half a century — as she wrote it exactly

Researching my book, MacArthur’s Spies, I tracked down Claire Phillips’s wartime diary, written in a small insurance company date book. This is the first of a series of blog entries featuring the diary — untouched for half a century — as she wrote it exactly

laire Phillips, the tough-living heroine of MacArthur’s Spies, did everything in her lifetime to cover up who she really was and how she kept alive in Japanese-occupied Manila during World War II.

laire Phillips, the tough-living heroine of MacArthur’s Spies, did everything in her lifetime to cover up who she really was and how she kept alive in Japanese-occupied Manila during World War II. accept — that she was the devoted wife of a man she had lost in the war. By the time a film was made about her life in 1951 — “I Was An American Spy” — the deception was complete. Claire was now an innocent widow drawn into battle and seeking revenge. She died at age fifty-two in 1960, a winner of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, but almost forgotten.

accept — that she was the devoted wife of a man she had lost in the war. By the time a film was made about her life in 1951 — “I Was An American Spy” — the deception was complete. Claire was now an innocent widow drawn into battle and seeking revenge. She died at age fifty-two in 1960, a winner of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, but almost forgotten.